I was out of my classroom yesterday, attending an AP Stats workshop with my coworker and friend, Dianna Hazelton. Upon my return, per the usual, I learned that students struggled with the assignment I left for them. Naturally, it would seem that the most important task to be completed today was to address their issues with yesterday’s work. But something much more important came up: a discussion on racism and sexism.

The natural opportunities to discuss race in a mathematics classroom in rural Minnesota are not numerous. I usually need to carefully weave them into the topics and diligently ensure that equity is valued when a student brings up situations of racism. The minority population in our district is not high but being the only student of color in a classroom is challenging for them. These students can’t be expected to just blend with their white classmates when their needs aren’t being addressed.

Somehow today, instead of practicing line graphing on whiteboards, we discussed race and gender when a student expressed her discomfort while attending a concert in Minneapolis. Her comments were respectful, but her concerns legitimate. As a teenage girl, when at social events in the city, she and her friends feel vulnerable and sometimes threatened by the sexual advances of men. She started off pointing out black men specifically, but the conversation progressed to a point where she acknowledged that first, her isolated experience shouldn’t shape a stereotype about all black men and secondly, white men engage in this behavior as well causing the same discomfort for her. She quickly realized that her assessment of dealing with harassment shouldn’t be examined through the lens of race.

Rafranz Davis, a woman whose fearless, relentless advocacy of kids I highly admire and respect, summed this up perfectly on her blog:

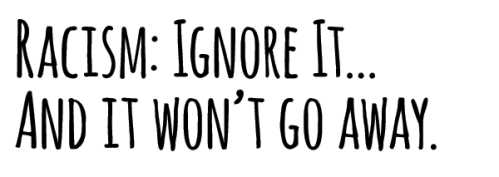

Students carry unique perspectives about their experiences and until these issues, along with the countless others unaddressed, are met head on through discussion and action, these tensions and perspectives will never change.

I was very proud of this student for acknowledging her initial prejudice, and as a result, we were able to have an equally productive conversation about gender as well. And something I didn’t expect happened: the boys just listened. They just listened to the girls talk about cat calls and being whistled at. “Just come and say hello, my name is so-and-so,” one girl said, “that’s much more of a turn on than being harassed.” And at the end of the class period, one of the boys went up to that girl and said, “hi my name is…” Bingo.

These conversations are difficult, but when a student is willing to admit their prejudice, the teacher doesn’t only have an opportunity, but a duty to help foster positive change. Graphing 3x + y = 10 can wait until tomorrow. The real problem of the day, and every day, is that these kids come to our schools for 7, 8, 9 hours a day and we spend such a small percentage of that time listening to their voices and giving value to who they are inside.